The Karolyi Dynasty and the Corruption of Academic Finance

''Are you proposing that the editor retracts the paper of his son? What's the point then of being the editor?''

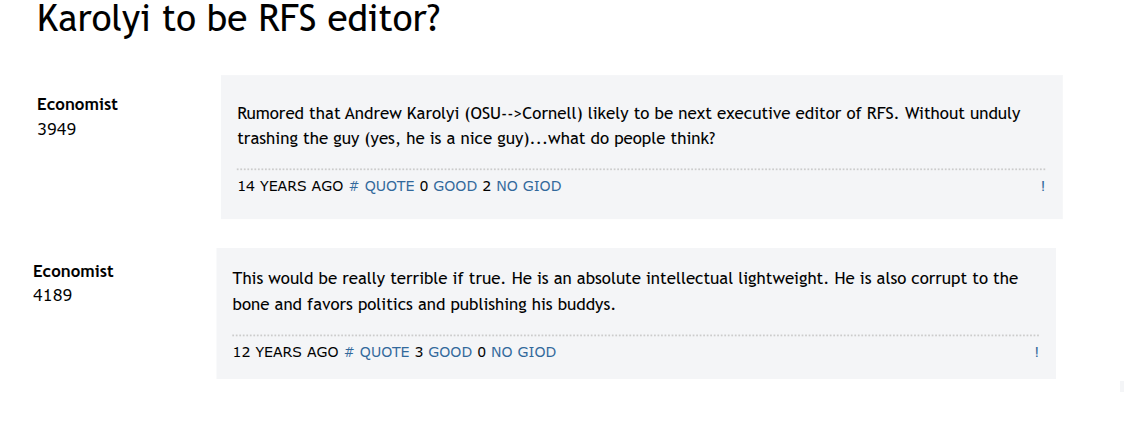

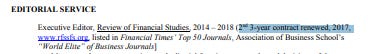

Fourteen years ago, Cornell finance professor Andrew Karolyi was appointed executive editor of the Review of Financial Studies—one of the three most powerful journals in the world for academic finance.

At the time, a lone commenter on EJMR accused him of being “corrupt to the bone” and ‘‘publishing his buddies.’’

What once sounded like an internet cheap shot now sounds like prophecy.

The Karolyi name has since become shorthand for everything rotten in academic finance: nepotism, backroom deals, and a profession that quietly rehabilitates insiders rather than holding them accountable, or even asks them to say sorry.

Before writing this article, I contacted both Andrew Karolyi, and his son, Stephen Karolyi (He/Him/His), but neither responded.

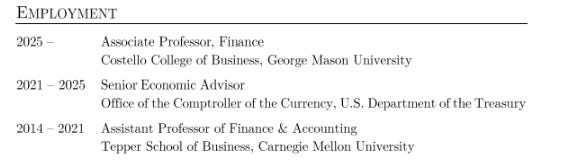

Stephen Karolyi earned his PhD in Financial Economics from Yale in 2014, landed his first tenure track job at Carnegie Mellon, then immediately began flooding the Review of Financial Studies with submissions, knowing full well that racking up multiple publications in his daddy’s journal would guarantee him a lifetime of tenured sinecures.

But publishing in daddy’s journal was only the tip of this corruption iceberg…

Will the real specification please stand up?

Our saga begins in October 2015, when our hero, an assistant professor of accounting named Alex Young—then at North Dakota State, now at Hofstra—attended a conference where Stephen Karolyi presented a paper, “Governance and Taxes: Evidence from Regression Discontinuity,” coauthored with Andrew Bird, another assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon.

The lowly North Dakota scholar spotted a fatal flaw with their methodology and alerted them, but the mighty Carnegie Mellon scholars brushed him off.

When that paper finally appeared in The Accounting Review in January 2017 — another one of the best accounting journals in the world — Young again spotted something odd: the methodology section had been rewritten since the 2015 draft… but every number in all 11 tables remained identical, down to the third decimal place.

Their methodology completely changed, but their results didn’t…

That is how they were caught.

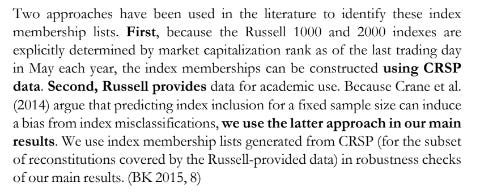

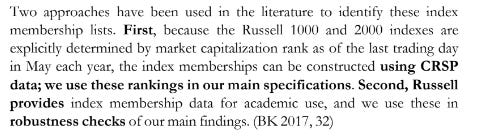

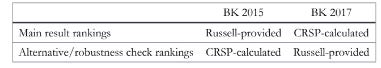

In the 2015 draft, the authors began their data description as follows:

In the 2017 draft, the authors stated that they made the opposite choice:

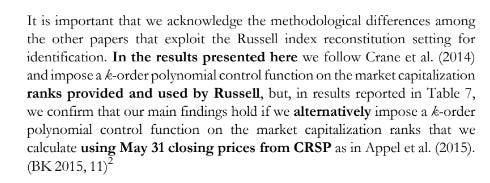

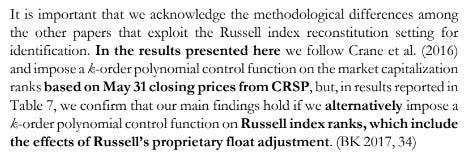

The 2015 methodology further appears the following:

While in 2017:

In sum:

Young concluded it was fraud:

Thus, if we compare the tables from the two versions, at the very least, we should see slightly different numbers for the estimated coefficients, standard errors, etc. But row for row, column for column, the numbers for the estimated coefficients, standard errors, and R-squareds are all exactly the same between BK 2015 and BK 2017 to three decimal places.

Young then launched a campaign to get to the bottom of it.

On 18 April 2017, Alex Young emailed Professor Bird to follow up on their October 2015 conversation, and requested that he share their data and code.

Two days later, on 20 April, Professor Karolyi replied with a short message that ignored the request.

On 5 May 2017, Alex Young then wrote to The Accounting Review, to explain his concerns in detail.

Six months then passed with no update.

In November 2017, Econ Journal Watch (www.econjorunalwatch), the profession’s most respected independent watchdog, intervened formally to request the files. The authors answered—but not with the files. The journal asked again. The answer was still no.

On December 1, 2017, The Accounting Review (TAR) formally opened a misconduct inquiry thus launching a series of elaborate excuses from Bird & Karolyi.

Excuse #1: The Copy-Editor Did It

One month later, in January 2018, Young published a devastating takedown in EconJournalWatch.

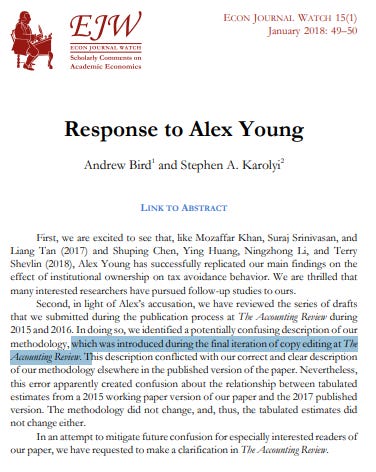

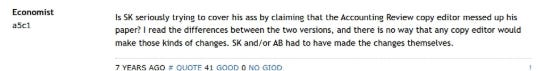

Bird & Karolyi responded immediately with a note blaming the ‘‘potentially confusing description of our methodology’’ on a rogue ‘‘copy editor’’ who made the changes ‘‘during the final iteration of copy editing’’ without their knowledge.

This claim is absurd.

Copy editors don’t rewrite methodology—they deal with commas, capitalization, and house style. They would never, under any circumstances, alter how you describe your data or your methods. And even if they did, every journal shows you exactly what edits the copy editor made, giving you the option to accept or reject them. Authors are wholly responsible for ensuring the text accurately reports their data and findings.

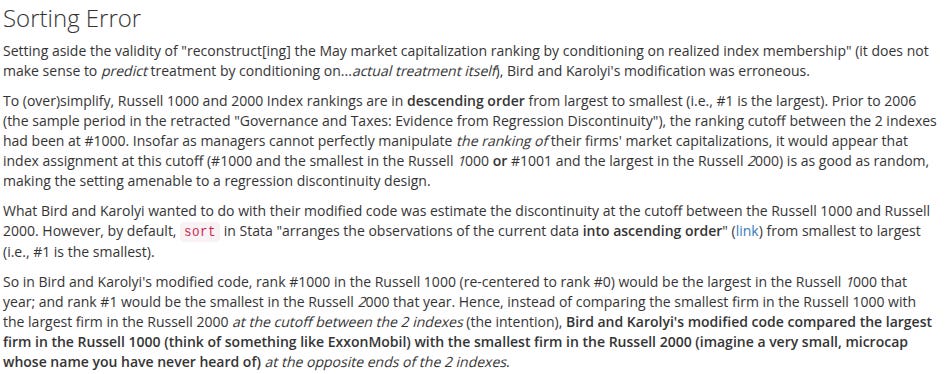

Excuse 2: STATA Sort

Nobody bought the ‘‘copy-editor’’ excuse, so, a month later, in February 2018, Bird and Karolyi published a (now deleted) 4-page note to SSRN titled, “Governance and Taxes: A Note on Methodology.” That note claimed that Alex Young did not correctly replicate their article:

Young (2018) replicates the main findings using the Russell rankings, but was unable to replicate the same finding using May market capitalization rankings.

Curiously, rather than open-sourcing their own data and code to prove Young wrong, they only used the data and code provided by Young:

To provide the strongest possible evidence of replicability, we replicate the main findings of Bird and Karolyi (2017) using only data and code provided by Young (2018). We do this by making one correction to the measurement of May market capitalization ranking

The correction they made to Alex Young’s data involved the STATA ‘‘Sort’’ command — and tweaking that ‘‘Sort’’ command magically fixed everything:

The following regression commands (exactly as in lines 51 and 52 of the Young (2018) code) produce analogous results using reconstructed May market capitalization rankings:

This is what their miraculous ‘‘Sort’’ fix looked like:

This would turn out to be fraudulent as well, because it sorted the data the opposite direction as they claimed. They got the coding backwards.

When I emailed Alex Young to ask about the ‘‘Sort’’ tweak, he uploaded an extensive explanation:

To be clear, if Andrew Bird and Stephen Karolyi had simply made a Stata

sortcoding error and had provided their original data and code which

contained this error and

reproduced all their reported tables in “Governance and Taxes: Evidence from Regression Discontinuity,”

I would’ve been convinced that they committed no data falsification. In addition, I would’ve apologized to them and contacted Dr. Daniel Klein to request that my Econ Journal Watch article be appended with a note clarifying that there was no research misconduct, just an honest mistake. Everyone makes mistakes, and of course I am no exception to that.

So the problem is not a mistake.

Within days of posting their flawed ‘‘Sort’’ fix, Bird and Karolyi deleted the 4-page SSRN note and replaced it with a shortened 1-page note that now contains:

no mention of their STATA sort tweak ever existing,

no mention of any data or any code,

no tables, and

no citation of any article besides their own.

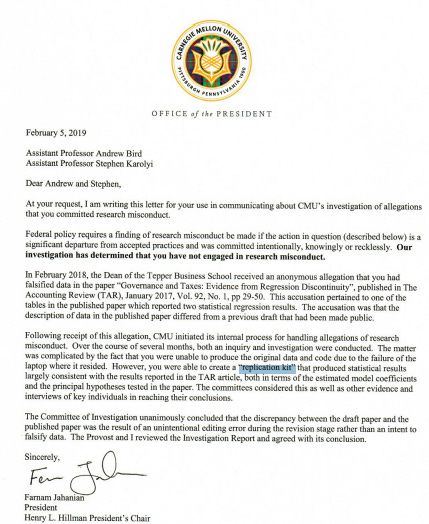

Excuse #3: The Dog Ate My Laptop

When The Accounting Review requested the data and code during their investigation, Karolyi & Bird claimed that a laptop crash had wiped out everything—no backups, no cloud storage.

The excuse was hard to believe given that Karolyi was known for managing numerous projects simultaneously; at that point, they had nearly 30 (!) working papers in progress, making it implausible that all their research, code, and data would have been stored on a single, unprotected laptop.

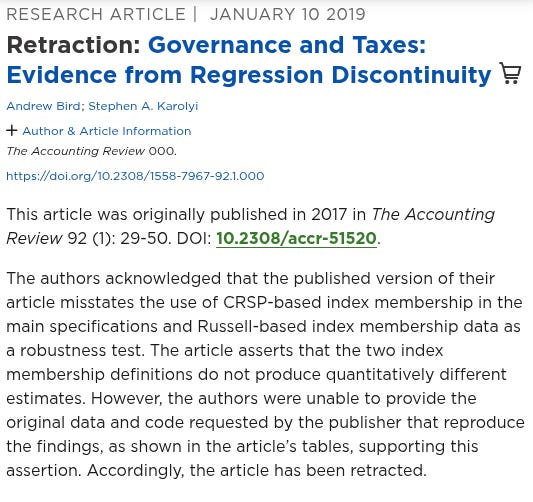

In 2019, The Accounting Review concluded their investigation and retracted the article, explicitly stating that “the methodology described in the paper does not generate the results reported,” and that ‘‘the authors were unable to provide the original data and code.’’

The Accounting Review‘s retraction notice does not mention Alex Young or comment on whether Bird and Karolyi committed any form of research misconduct.

Bird & Karolyi admitted no wrongdoing: they put out a statement saying that they ‘‘are disappointed by the American Accounting Association’s (AAA) decision.’’

They maintain they committed no fraud and thus no crime.

The dog just ate their laptop, that’s all.

Stephen Karolyi’s CV now has a cheeky section referring to this retracted paper as a ‘‘Permanent Working Paper’’:

Excuse #4: The Replication Kit

Following The Accounting Review’s retraction, Carnegie Mellon’s Office of Research Integrity and Compliance (ORIC) launched an investigation at the Provost’s request. ORIC found “no evidence of research misconduct,” reasoning that although the authors had “lost” their original data and code, they were able to privately “create a replication kit” that reproduced the results. They refused to release the alleged replication kit, preventing anyone from verifying this claim.

After being officially ‘‘cleared’’ by CMU, Andrew Bird was exiled from the school without tenure — yet soon resurfaced at Chapman University, with tenure.

I spoke to Alex Young about Dr. Bird’s transition to Chapman University, he told me:

From November 2020 to September 2023, I received multiple emails from [name retraced], formerly Associate Dean for Research at Chapman University’s business school, “seeking input.” [name retraced] brought up the “replication kit” claim, and I asked him three times (in November 2020, March 2023, and September 2023) for a copy of the “kit.” [name retraced] ignored my first request and then responded to my last two requests by saying that he did not have “access” to the “kit,” or any interest in obtaining “access.”

I reached out to [name retracted], who denied this version of events but was unable to substantiate his recollection after changing jobs and losing access to his old emails. His explanation nonetheless seemed credible, so I withdrew his name from this article.

Excuse #5: Daddy’s Corrigendum

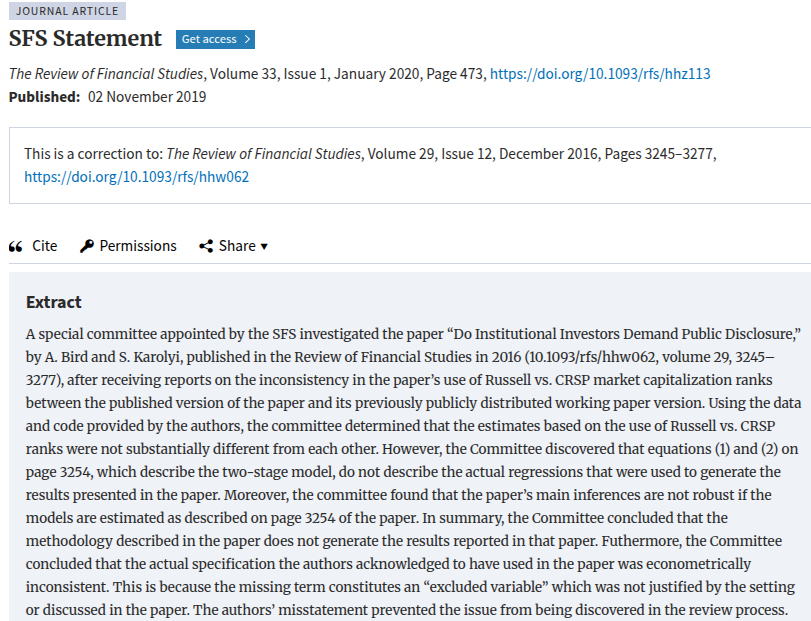

After being caught red-handed fabricating results in The Accounting Review, Bird and Karolyi were exposed a second time when a special committee appointed by the Review of Financial Studies — managed by Karolyi’s father, remember — investigated their paper, “Do Institutional Investors Demand Public Disclosure”, after ‘‘discovering inconsistencies between the published version and the earlier working paper.’’

Using the data and code provided by the authors, Review of Financial Studies determined that two versions of this paper used different market capitalization rankings (Russell vs. CRSP), yet somehow produced identical results.

In other words, the Review of Financial Studies paper suffered from the exact same fatal flaw as their The Accounting Review paper: the description of the specifications had changed, but the numbers in every table magically stayed the same.

After Review of Financial Studies concluded that the same ‘‘error’’ happened a second time, they published a “Statement” concluding that:

“the Committee discovered that equations (1) and (2) on page 3254, which describe the two-stage model, do not describe the actual regressions that were used to generate the results presented in the paper.”

“the committee found that the paper’s main inferences are not robust if the models are estimated as described on page 3254 of the paper.”

“the Committee concluded that the methodology described in the paper does not generate the results reported in that paper.”

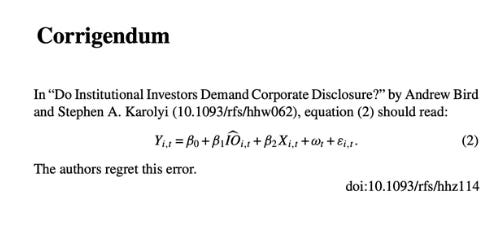

In response, the authors quietly published a paywalled corrigendum admitting the fatal flaw, noting only that “the authors regret this error” and that their methods were were wrong.

The paper remains on the books, unretracted, still padding their CVs and tenure files. Daddy refused to retract it, and instead let them publish a bogus corrigendum.

It’s hard to explain why the same “mistake” happened twice. That’s blatant fraud.

In any honest system, that ends a career.

In academic finance, it’s just another Tuesday.

‘‘The bottom line, it seems, is that Bird and Karolyi appear to be unable adequately to explain their research methods in ways that stand up to scrutiny.’’

“They are stealing journal space from honest researchers. This is not a victimless crime.’’

— Anonymous Economist

Consequences

Andrew Bird downgraded from Carnegie Mellon to Chapman University.

His co-author, Stephen Karolyi, meanwhile, was effectively exiled from academia and got a job in government as a “senior advisor” in the Division of Supervision, Risk, and Analysis at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

The man deemed too corrupt to remain in academia was entrusted with regulating the banking industry.

This brings me to why I wrote this article today.

On one level, this scandal is old news — relegated to obscure 2018 lore within the economics profession, never picked up by the media. I wanted to be the first to document it to show how the sausage is made.

But the timeliness is what makes it relevant: as of last month, Stephen Karolyi has now returning to academia, moving from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency to tenure at George Mason University’s business school.

The obvious question is: can someone who committed blatant academic fraud, and had his nepo daddy sweep it up, ever be redeemed? Or is there a line beyond which “second chances” become a joke — especially when every single one of his colleagues is aware of his fraud?

“It’s one thing if you hire someone that turns out to be a fraud. It’s another to hire a known fraud. Embarrassing for GMU faculty and really the profession overall. I thought some of the people at GMU were respectable, but not at this point.”

— Anonymous Economist

What message does hiring him send to students?

Is he going to tell them with a straight face that he ‘‘lost his laptop’’ when they ask him about this fraud?

Or will he go back to blaming it on STATA?

Or will he go back to blaming it on the copy-editor?

The simple truth is that Dr. Stephen Karolyi would not be a tenured professor today if his powerful daddy didn’t protect him, and if his colleagues cared about unrepentant fraud. For students, early-career researchers, and anyone who believes in meritocracy and scholarship, this is a bitter pill to swallow. While unrepentant frausters like Stephen Karolyi are given infinite “redos,” countless honest economists grind away for years, hoping hard work will be enough to secure a stable academic career.

The lesson is clear: the system is corrupt.

No wonder the profession is dying.

As for the elder Karolyi, who enabled his son’s fraud, his CV shows that he was renewed in 2017 for a second three-year term as an executive editor of the Review of Financial Studies. He “voluntarily” resigned from this position only one year into that term, in 2018, right as his son was put under investigation.

Excellent work. I think it's time social "sciences" are eliminated entirely from education. They have brought nothing good to civilization.

The part about GMU hiring him back really undercores how these institutions priortize reputations over accountability. When someone with this track record can just move from one tenured position to another, it sends a clear mesage that the barriers to entry aren't about integrity. Young basically had to wage a one-man campaign to expose this, and even then the system barely responded.