Elsevier Shuts Down Its Finance Journal Citation Cartel

12 papers retracted, 7 editor positions removed, and the "open secret" of Elsevier’s elite paper mill exposed.

On Christmas Eve, 9 “peer-reviewed” economics papers were quietly retracted by Elsevier, the world’s largest academic publisher.

This includes 7 papers in the International Review of Financial Analysis (a good journal—it has an 18% acceptance rate):

RETRACTED: Financing Irish high-tech SMEs: The analysis of capital structure

RETRACTED: Extreme spillovers across Asian-Pacific currencies: A quantile-based analysis

RETRACTED: Identifying the multiscale financial contagion in precious metal markets

RETRACTED: Is Bitcoin a better safe-haven investment than gold and commodities?

RETRACTED: Cryptocurrencies as a financial asset: A systematic analysis

Plus two more retractions in Finance Research Letters (29% acceptance rate):

Two days later, three more papers were retracted at the International Review of Economics & Finance (30% acceptance rate):

RETRACTED: Oil price shocks and yield curve dynamics in emerging markets

RETRACTED: ESG disclosure and internal pay gap: Empirical evidence from China

Combined, these 12 papers have 5,104 citations.

All 12 papers had one thing in common: Brian M Lucey, Professor of International Finance and Commodities, Trinity College Dublin — the #1 ranked economics and business school in Ireland — as a co-author.

Lucey published 56 papers in 2025, one paper every 6.5 days. Lmao.

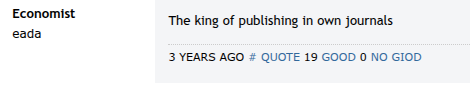

Lucey has published 44 papers in Finance Research Letters alone, an Elsevier journal he edited.

I emailed Lucey for comment, but he did not respond.

Brian Lucey… where have I heard that name before?

Oh yeah, he bullied me on Twitter in 2023.

‘If you wait by the river long enough, the bodies of your enemies will float by.’

— Sun Tzu

The stated reason for the retractions was that: “review of this submission was overseen, and the final decision was made, by the Editor Brian Lucey, despite his role as a co-author of the manuscript. This compromised the editorial process and breached the journal’s policies.”

In plain terms, Lucey was serving as editor while approving his own papers. The result was a complete bypass of peer review—an abuse of editorial authority that functioned as a citation-cartel scheme.

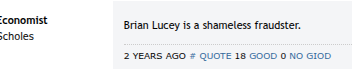

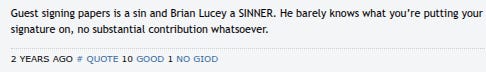

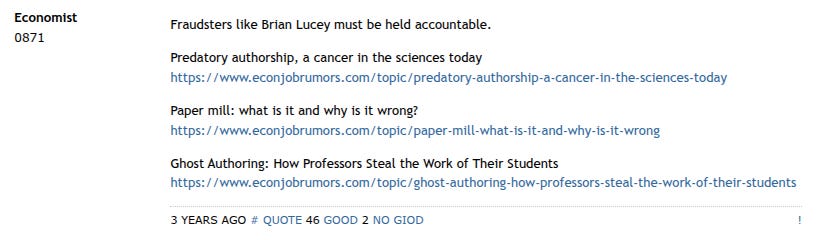

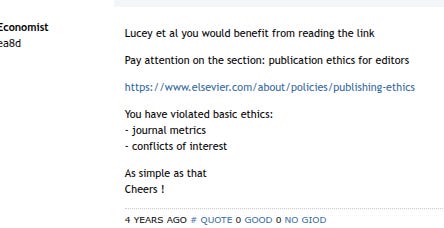

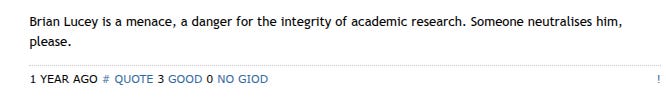

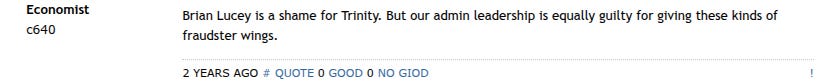

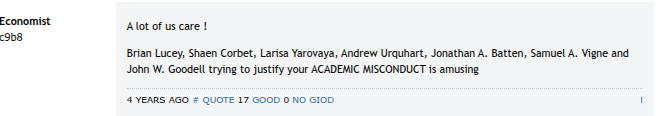

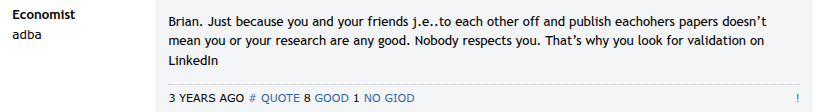

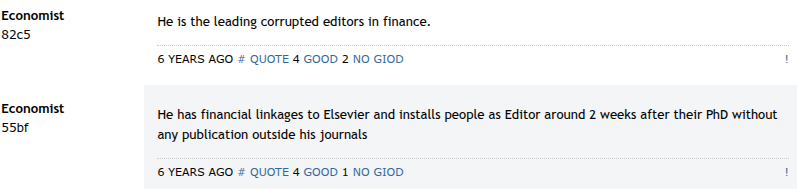

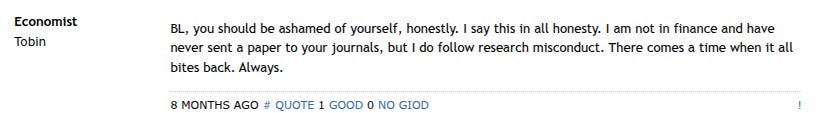

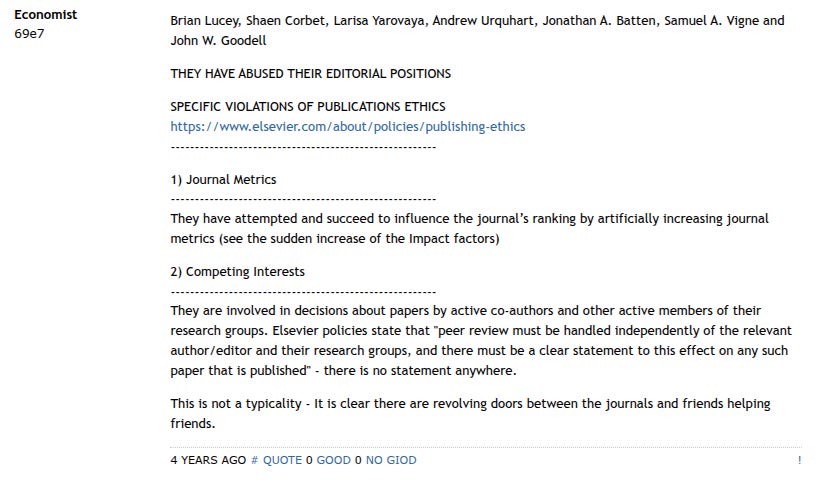

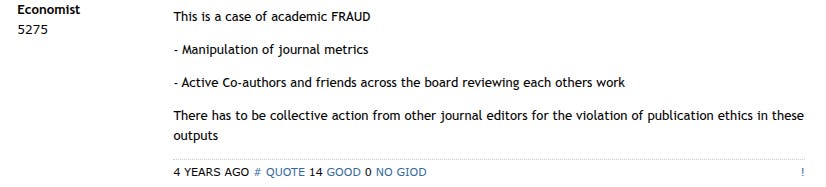

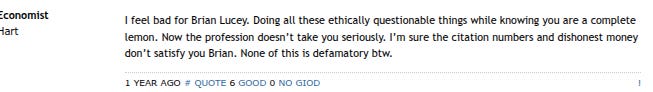

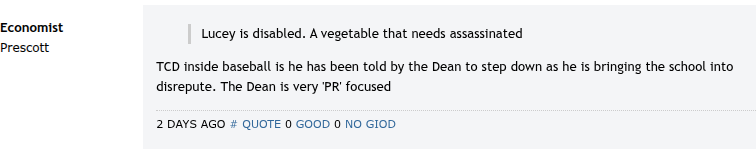

Apparently this was an open secret in the profession for many years, with EJMR comments going back 5+ years explicitly calling him out as a cheater:

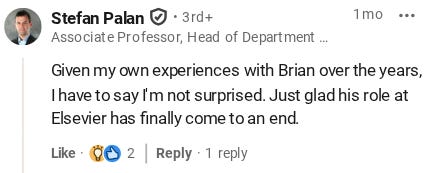

Along with the 12 retractions, Lucey was removed as an editor at 5 journals: International Review of Financial Analysis, the International Review of Economics & Finance, Finance Research Letters, Financial Management, & Energy Finance.

Lucey remains as editor-in-chief at Wiley’s Journal of Economic Surveys.

I emailed Wiley, and they provided me with this statement:

We are aware of these concerns and have investigated Prof. Lucey’s activity on Journal of Economic Surveys. Our research integrity team did not find any concerns regarding conflict of interest or mishandling of papers, nor has Prof. Lucey published any papers in the journal since he joined the editorial team as a co-editor in 2024. We expect full commitment and adherence to our editorial practices and standards, and we will be monitoring the situation to ensure that there is no improper handling of papers at the journal.

In response to Wiley’s statement, one EMJR user wrote: “I am baffled how they could possibly still have confidence in him, given his serious and systematic ethical lapses in editorial positions. Sounds somewhat naive to expect ‘full adherence to our editorial practices and standards’!”

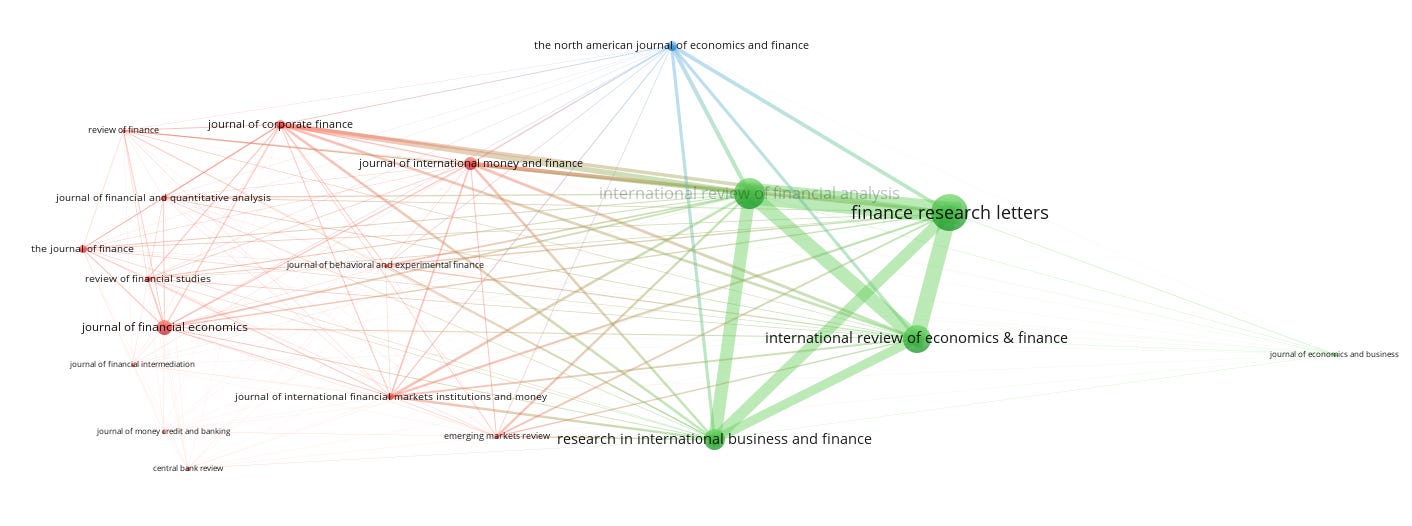

Until being purged from the leadership of these 5 journals, Lucey played a central role in coordinating Elsevier’s Finance Journals Ecosystem, which allows “participating journals to suggest transferring a rejected manuscript to another journal in the system without the need for resubmission and the associated cost."

That system, and the editors involved, “came under fire last year when a preprint suggested it might facilitate citation stacking as a way to boost journal impact factors. The analysis in the preprint also suggested a citation ring involving Elsevier editors could be at work.”

I emailed the anonymous “Theophilos Nomos” who wrote this paper, but they did not respond to my email.

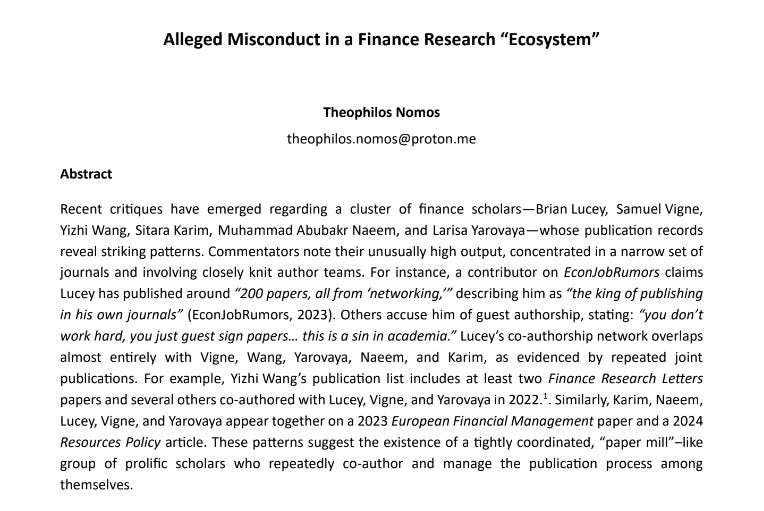

That pre-print names Samuel Vigne, a finance professor at Luiss Business School, former PhD student of Lucey, and prolific Lucey co-author (they have published at least 33 papers together) as a core node of Lucey’s citation cartel.

Multiple publications by Vigne and Lucey are flagged on PubPeer.

https://pubpeer.com/search?q=samuel+vigne (21 results)

https://pubpeer.com/search?q=brian+lucey (55 results)

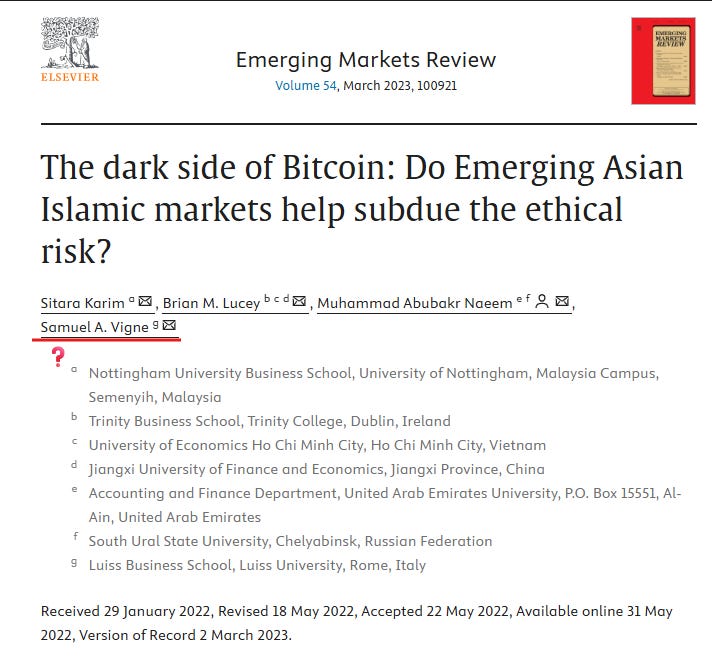

This example neatly illustrates how their co-authorship trading scheme operated:

It describes a draft uploaded to SSRN with three authors:

After submitting that draft to the Elsevier finance ecosystem, that draft was scrubbed from SSRN, and in the final published version, an additional author (Samuel Vigne) was added as a new author, with an “equal contribution” statement. The two versions are otherwise identical, containing the same figures, sections, and text.

Co-authorship trading is only one part of the operation. The other is citation stacking. In this model, a small, tightly linked group funnels an enormous volume of papers into the same handful of journals, then systematically stuffs those papers with citations to one another. The result is a rapid, artificial explosion in citation counts that makes them look like influential geniuses.

Take John Gooddell, a professor at the University of Akron and a Lucey co-author. Gooddell has published 68 papers in Finance Research Letters alone, a journal edited by Lucey. If each paper contains even a modest 50 references, that amounts to roughly 3,400 citations recycled through a single outlet. In 2024 alone, Gooddell published 61 papers. He’s not doing research. He’s farming citations.

Following Lucey’s retractions, Samuel Vigne was removed as the editor-in-chief of International Review of Financial Analysis and Finance Research Letters.

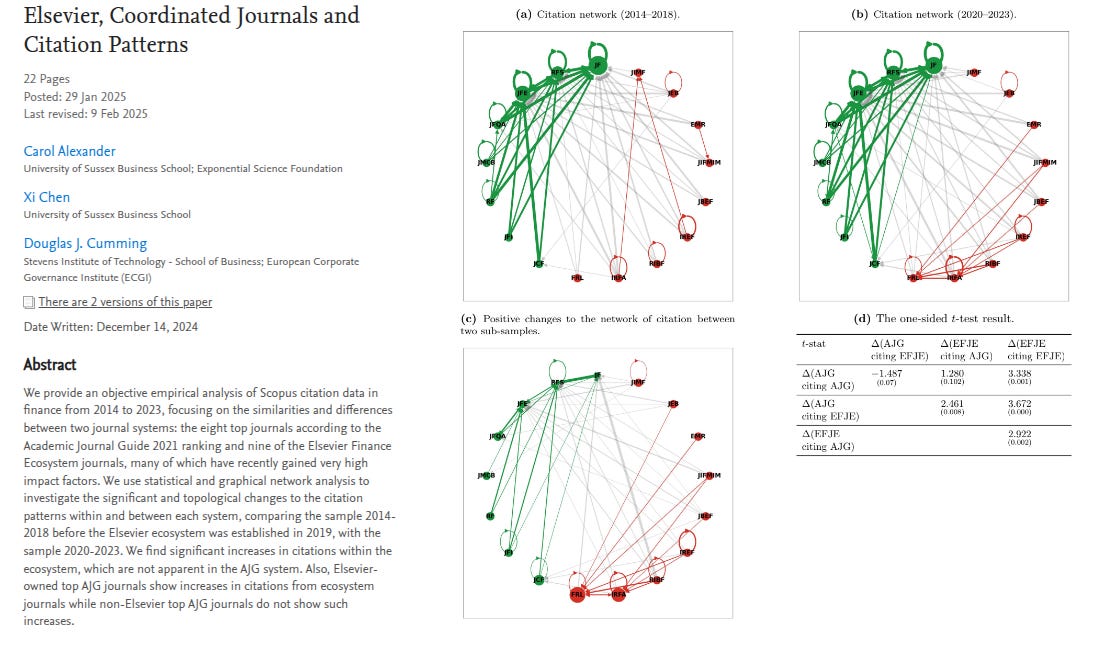

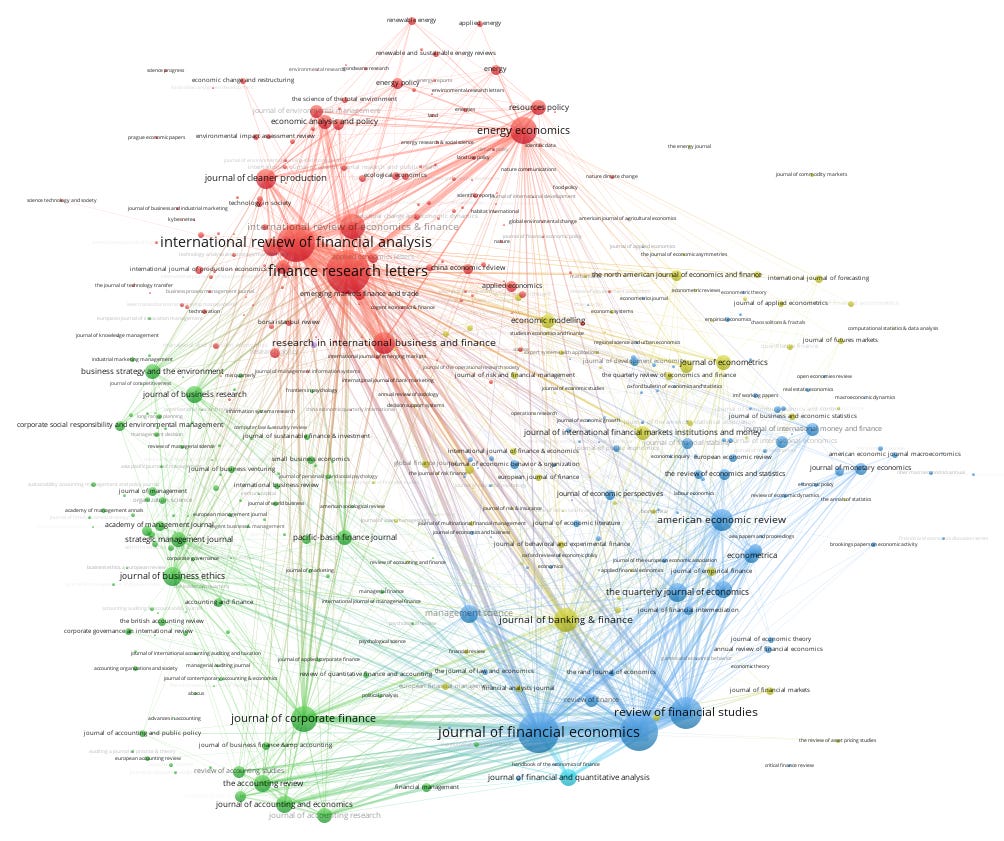

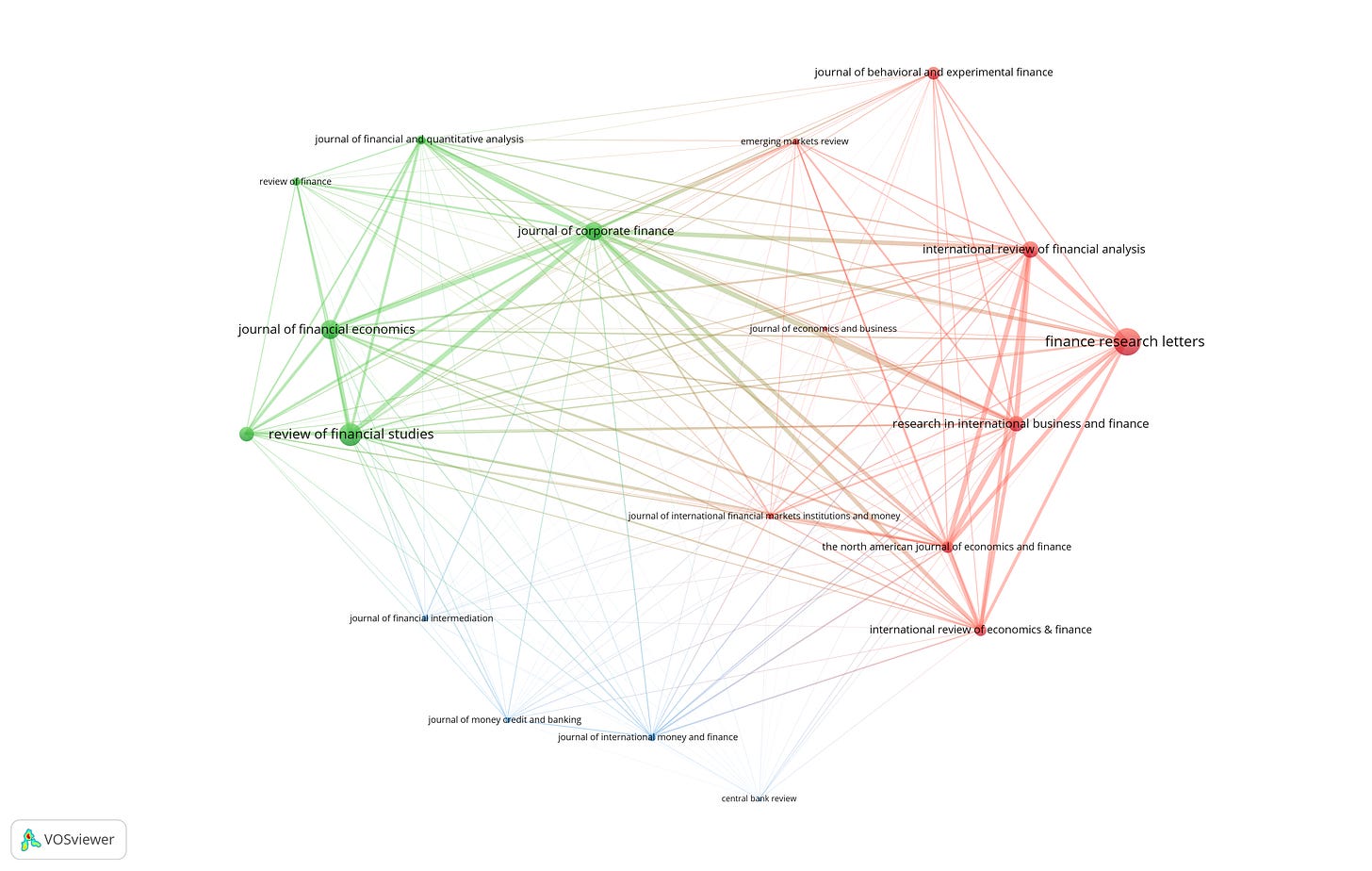

In addition to that anonymous pre-print, there is also a 2025 paper written by actual professors with sophisticated econometric analysis & graph theory which describes the citation cartel in much more detail. The conclusion of that paper is: ”Elsevier ecosystem journals benefited from the creation of the ecosystem … Elsevier journals in the ecosystem have overlapping editors and Elsevier appoints these editors in coordination with a single academic [Brian Lucey] that manages the fleet of ecosystem journals.”

Brian Lucey posted a reply to this paper, which was extremely weak and does not contain any tables or figures. It mostly ignores the data and structural model of the citation ring and instead leans on Lucey’s “lived experience” as an editor (“we have experience shepherding…”), while also nitpicking semantics and phrasing, such as Lucey complaining that they called him a “professor of finance” instead of his full honorific, “professor of international finance and commodities.”

The Elsevier ecosystem web page went live on 4 November 2020 , according to Lucey’s rebuttal. Below is a visualization of the network before and after this transition date, which shows a clear distortion of the citation network. During 2021-2025, the Ecosystem citations per article is 103 % higher.

2016-2020: (Before)

2021-2025: (After)

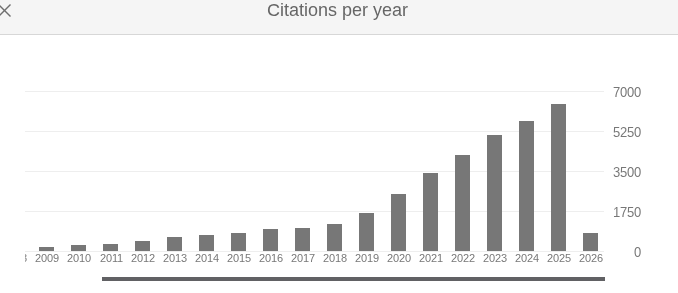

2020 is also the year where Brian Lucey’s citation profile exhibits an exponential “J-curve”, a Hallmark of citation rings. Did he suddenly become a well-respected genius in 2020? Or did he figure out how to cheat the system?

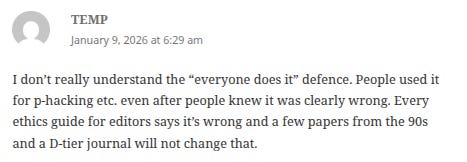

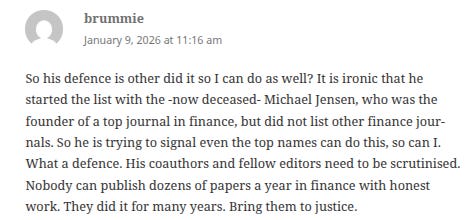

In a comment to Retraction Watch, Lucey further argued that citation cartels are not a crime, because everyone does it.

”Because here’s the thing: Elsevier are aware of [editors publishing in their own journals] as a pretty common practice in finance and economics. We’ve given them evidence of hundreds of instances of this. And nothing has happened, which does raise the question, you know, maybe they’re going to go back and go look at all these. Presumably, they will treat everything the same.” Lucey shared his list of such instances. It includes 240 articles, 133 of which are in Science of the Total Environment, which was delisted from Clarivate’s Web of Science in November.

(N.B.: As several commenters have noted, the list linked above includes citations to editorials and special issue introductions, which are typically penned by editors-in-chief. The disclaimer at the top of the document Lucey provided reads, “In no way is this meant to suggest any ethical or other breaches. It is a list of persons who occupied a EiC or similar role in the Journal mentioned at the same time as a paper in which they were an author or coautho[r].”)

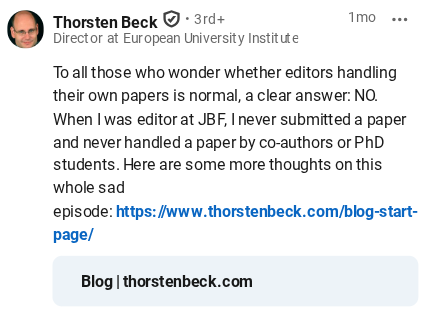

Dr. Thorsten Beck, in a blog post, confirmed that no, not everyone does it, and yes, it is a crime.

This incident raises an important question: is this common practice across academic journals? And are there rules for editors publishing in ‘their’ journals? As I was editor across three journals for a total of 11 years, I can certainly speak to this (and clearly say NO).

…

I don’t have formal confirmation but I have been told by several independent sources that ultimately even Elsevier realised that this editor was seriously damaging the reputation of the journal, appointing a second editor and then easing out the ‘doubtful’ editor from his responsibilities.

The fallout from the Lucey–Vigne era extends far beyond a handful of retracted PDFs. What it exposes is a structural weakness in how academic “excellence” is manufactured, measured, and monetized. By presiding over a coordinated cluster of journals, a small group of editors effectively gained the ability to print their own academic currency.

However, blaming Lucey and Vigne alone ignores the hand that fed them. Elsevier did not just “allow” this to happen; they engineered the environment for it to flourish, because of incentives: Elsevier’s internal metrics (Impact Factors) directly benefitted from this behavior. It was a symbiotic corruption: the editors received a fast-track to academic stardom, and Elsevier received a high-margin, high-volume production line of citable content.

This is the “paper mill” reimagined for the elite: not a basement operation in a third-world nation, but a polished, corporate-mandated factory within the halls o the world’s most powerful publisher. This is the natural result of a corporate mandate to maximize profits by bundling journals into monopoly-priced packages, forcing universities to pay for the very “prestige” that Elsevier’s own staff helped to dilute. As one EJMR commenter noted, “The tragedy isn’t that they cheated; it’s that the system was designed to let them thrive for a decade before anyone bothered to look at the data.”

The question now is whether Trinity College Dublin will fire Lucey.

They did not respond to my inquiry.

What Investigators Should Look For

An editor of a psychology journal was offered $1,500 per accepted paper.

Richard Tol, a professor of economics at the University of Sussex, wrote that he was offered $5,000 per paper.

Muhammad Ali Nasir, a professor of Macroeconomics at Leeds University, wrote about how common selling papers is in European finance journals: “I had been made such offers from anonymous emails but I choose not to engage and in one case forwarded the email to EiC. I will be surprised if any editor is not approached by these people.”

This raises a multi-million-euro question: given their documented corruption, are the various “educational consultancies” and special-purpose vehicles operated by Brian Lucey and Samuel Vigne used to circulate ecosystem funds, conference fees, or “consultancy” payouts from authors seeking a shortcut to publication?

One anonymous economist says:

Here is a hypothetical outline of how such a cash-flow scheme could function.

“Hello [unknown, distant institutions], we offer consulting services: €€€ for excellent advice on how to publish in top-tier finance journals. Our advice yields results.”

Money flows into companies.

Papers flow into journals.

Another anonymous economist says:

I’m not going to provide details on how to corruptly have a paper published. I’m just going to speculate on what could be going on in a situation like this. It could be based on “consultancy fees” for advice on publishing that you or your institution pay to one of those companies. They give some advice, including what papers to cite, etc, and if you follow their advice you are likely to be published in one of their journals. This could be attractive for researchers and institutions in, e.g., China and the Middle East.

Another anonymous economics professor I spoke to told me:

Universities in East and West Asia pay cash bonuses for publications. Some authors hire a broker (many advertise openly on Facebook), other authors contact the editor directly. The cash bonus is shared between the author, broker, and editor.

Besides selling papers, they also sell special issues, which allow the guest editors to do what they want.

And they sell positions on the editorial board, which are important for promotion to the next academic rank.

Some payments are in cash, others in kind.

Finally, they organize conferences. Registration fees more than cover the costs of putting on a conference. The conference name suggests it is organized by a society, but it really is Lucey who pockets the profits.

Brian Lucey and Samuel Vigne operate four private companies in Ireland and the UK classified under “other education,” likely functioning as consultancies or special-purpose vehicles for academic or policy work.

INTERNATIONAL CLIMATE FINANCE VENTURES COMPANY LIMITED BY GUARANTEE

FUTURE FINANCE AND ECONOMICS ASSOCIATION LIMITED

The existence of these consultancies warrants investigation into potential conflicts of interest and financial misconduct.